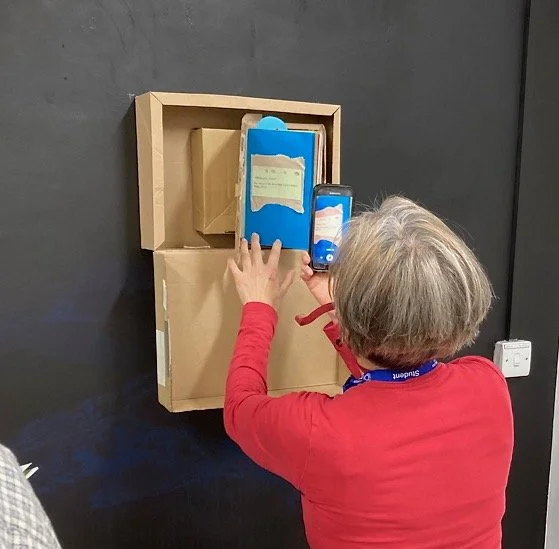

Experimenting with making stands and armatures for the freestanding elements, I understand more about the characteristics of cardboard, and what can and can’t be done with it. The warp and weft of the material, thanks to the flutes that comprise its inner layer, dictates its malleability, whether using a knife or one’s hands. Cutting a line in the flute’s direction (warp) is smooth and quick, but slicing through the flutes (weft) requires more patience and strength, often producing unplanned rips and tears. Although frustrating at first, I view these as happy accidents that allow me to stop and reconfigure my plans. Such rips and tears add character to the bland cardboard that, in turn, invites a haptic response from the viewer, along with the pleasure that comes from the sound and action of ripping and tearing. This aspect is evident in the work of Eva Jospin.

Cardboard flutes are revealed by cutting top layer with a Stanley knife to create bark. Photo Shirley A

Creating bark by scraping the underside of cardboard with a closed pair of scissors. Photo Shirley A