This was a challenging year for me, both physically and mentally, as I continued to battle with Long Covid, a dislocating knee and arthritis, which all affected my studio practice. Painful and awkward they are, but ironically these conditions helped in my exploration of coping with tense situations. From this, I developed a mantra that helps me personally and with my practice: recognise strengths and weaknesses, step back; rest; contemplate; look at the situation anew; go forward.

Regarding the development of the major project, I kept returning to Freud and Laing’s theories on the effects that family and friends have on the psyche, and Klein’s view that children express their anxieties through play. As I worked in the studio, the psyche of the child was always in mind as I tried to recapture their innocence, freshness and natural curiosity – the same qualities that Dubuffet sought with outsider artists, and that Matisse’s paper cutouts showed, as well as a sense of fun.

Studio days, where much of the time is spent watching paint dry… and thinking, reflecting, evaluating. Photo Shirley A

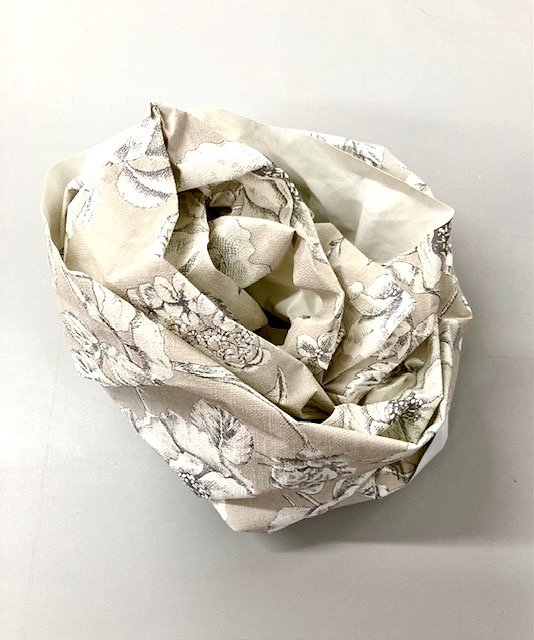

The project’s context came from comparing my own childhood experiences of how I coped in uncomfortable situations with how I handled the Covid 19 lockdowns: as a child, I would make dens to create my own safe space to contemplate the world; as an adult restricted to the home and recovering from Covid, I undertook small, gentle origami projects, which became pop-up sketchbooks that were encased in recycled mailer envelopes. The garden became my sanctuary – my grown-up ‘den’ – and from this I introduced a horticultural aesthetic to my project.

Supporting my academic reading were the novels I read through the Covid lockdowns, which included childhood favourites such as Robinson Crusoe, The Secret Garden and The Little Princess, biographies of real-life pioneers (Cougar Annie), as well as a mix of Japanese literature such as In Praise of Shadows and the more contemporary People from My Neighbourhood and Before the Coffee Gets Cold, which tie in with my interests in Japanese culture.

In converting all this into a major project, I considered scaling up the pop-up books into a giant one, and experimented with other paper-based packaging materials. Throughout the process, dilemmas constantly plagued me: Do I carry on with hand-sized pop-ups? What about building a pop-up book that is in itself a huge sculpture? Do I have the giant pop-up on its own (and possibly involve it as a performance) or, continuing my previous projects, set it within an installation? What is sculpture – what is an installation? Paper or cardboard – wallpaper, multiple envelopes? I thought I knew what the characteristics of these materials, so why don’t they do what I want?

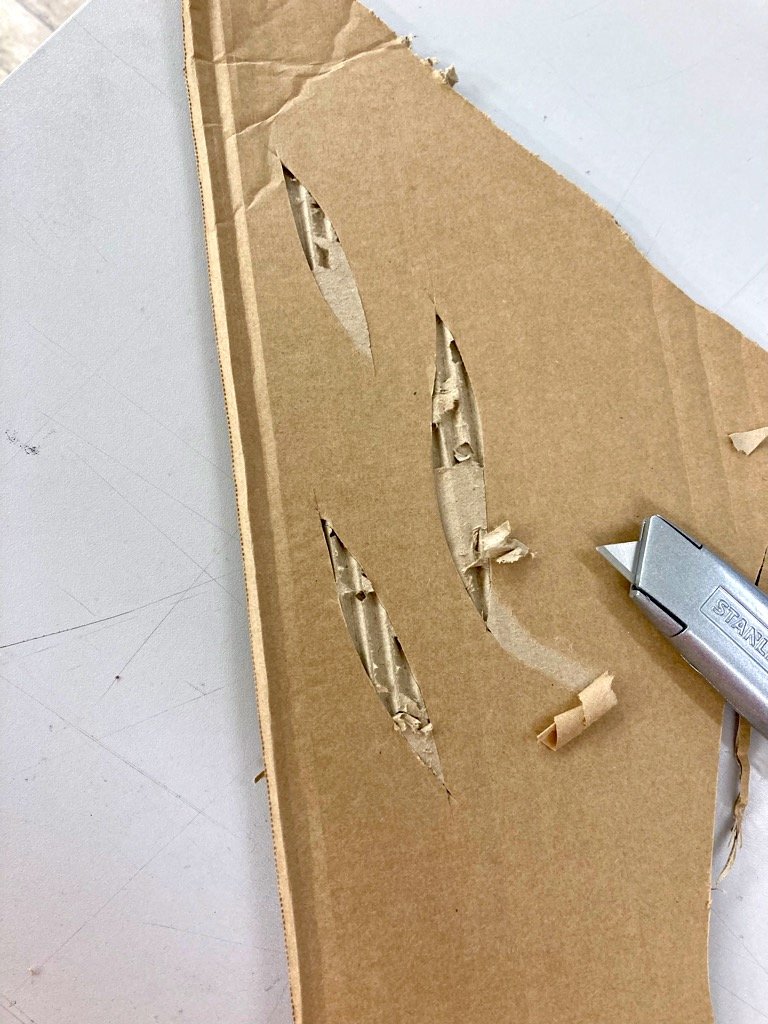

The last query was key. For the Winter Show, I’d produced a cardboard trees installation to test it as an environment for a pop-up book. Although it was very much a work in progress, I was pleased with the reactions of visitors as they walked through, using their whole bodies to view the pieces – up, down and around. The big problem I had with these flat trees was in their making: cutting through cardboard’s fluted sections for several weeks triggered an arthritis flare-up that continues today. Another frustration was trying to control them, as they kept flopping over when I moved them, leaving creases that diminished their strength.

Cutting through cardboard to reveal the flutes. Doing this for prolonged periods is hard on the hands. Photo Shirley A

This coincided with another challenge that was beyond my control when I came back after the Christmas break and found the studio in chaos and that decorators had damaged my work. I was at a loss as how to continue my project. But, after a period of contemplation, per my mantra, I switched medium to kraft paper, thanks to visiting lecturer Julie Hill, who uses paper to make monumental structures. This marked a turning point in my practice: while kraft paper has a similar bland aesthetic to cardboard, it is lighter, easier to source and much more malleable. In turn, I felt lighter, energised and once again excited to make works on a larger scale – without pain.

Organised chaos. Turning this into a work of art - or is this it? Photo Shirley A

This was also aided by being given a studio space in the main seminar room, due to my mobility issues. This was a privilege that I took advantage of, expanding my designated area as my work got bigger. But here, timing and planning were key, as I had to share the room when lectures and workshops took place, which meant that I had to stop the noisy and awkward activities of crushing and painting 25m rolls of paper, then waiting for them to dry, before more crushing and moulding them into shape. So, most of the big, noisy stuff was done on Saturdays, when I had the room to myself.

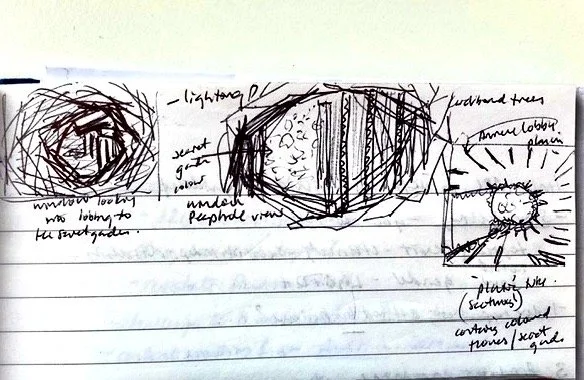

Doodles in a work notebook contribute to the archive of thought behind the project. Photo Shirley A

My key takeaway from LMU’s BA Fine Art course is understanding that my practice is intertwined with everyday life, which began with the ‘Ways of Seeing’ module in first year. There is no separation. Whatever I do and see, or happens to me will affect my art, whether that’s health matters, studio disasters, going to exhibitions, travelling to Japan, taking a walk around my neighbourhood or pottering about the garden.

Penge meets Songenchi… although I’m sure this contorted tree wasn’t the result of centuries-old manipulation by Buddhist monks. Photo Shirley A

South London’s spring palette, inspiration from the local neighbourhood. Photo Shirley A

Sad as I am to leave the safe nest of university, I’m looking forward (with some trepidation, admittedly) to a new beginning. Having documented my work in notebooks, blogs, sketches and maquettes will be a good foundation for whatever I do next. During summer I shall be researching residencies and looking for a studio that I can share with like-minded artists – one that will cope with my ever-expanding practice.